The history of the breed

The origin of the bengal catThe origin of the bengal cat

Bengals are a hybrid breed

Bengals are one of the most spectacular cats because of their shining tabby coats, which provide the exotic appearance, combined with the character of a domesticated cat. Bengals are a hybrid breed created from a cross between the Asian Leopard cat (ALC) and a domesticated cat. The Asian leopard cat is a wild cat of about 4kg, 40cm long excluding a tail of 20cm. Its habitat is Southeast Asia

The first mention of bengals

The first known reference to hybrid cats goes back to the world’s first cat show in 1871 at The Crystal Palace in London, staged by Harrison Weir. During that show, Persians, Angoras, Manx, Abyssinians and Siamese were on exhibition. In addition to these breeds, there were other classes, including“domestic cats crossed with feral cats.” Harrison Weir also set the standard by which the exhibits were judged against. In his 1889 book “Our Cats and All At Them,” Harrison writes about a spotted tabby hybrid cat, which originated from a cross with a “wild cat of Bengal”. It was not until 1924, in a scientific journal in Belgian, that the next recorded reference to the breed occurred. Then, in 1941, there was an article printed in a Japanese cat publication mentioning that one was kept as a pet.

Three main characters driving the development of the Bengal

The development of the bengal is largely due to three individuals. Bill Engler, owner of a zoo and advocate for the protection of exotic cats, was the first to succeed in breeding second- and third-generation bengals and is known as the one who established the breed’s name with various breed cat associations. Willard Centerwall is a geneticist who has done much research on ALCs and was instrumental in providing cats to Jean Mill. Jean Mill was a passionate breeder of hybrid cats. She is the one, who first succeeded in further breeding bengal to the fully domesticated variety. As a champion of bengal and her relentless promotion of the breed, she is the true founder of the modern bengal breed.

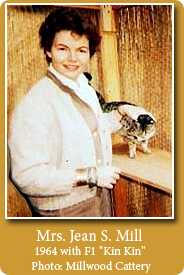

Jean Mills first adventure

Jean Mill (née Jean Sugden), from Des Moines, attended Pomona College in California to study psychology. In 1946, she took several master classes in genetics at UC Davis. There she suggests crossing Siamese and Persian cats to create so-called “Panda Bear” cats. These are known today as Himalayas. She starts with this in 1948, in 1954 she creates the Himalayan breed and in 1960 she shows her award-winning cats. Her proposal to the AFCA in 1965 to get the breed recognized stranded, however, because the board was made up of 50% Persian breeders and 50% Siamese breeders, neither of whom were fans of crossing the breeds.

On to the next adventure

In 1961, Jean Mill imports an ALC called Malaysia. The ALC feeling somewhat displaced on her ranch in Arizona, she decides to give it the company of a black tomcat. To her and (everyone else’s) surprise, the animals mate and a litter ensued of two kittens. The male kitten does not survive, but the female KinKin can be rescued and grows up with a litter of Himalayas. She bred KinKin back to the father (there was no other suitable available) and two more kittens were born: a nasty tempered daughter (Pantharette) and a son who sadly died after a fall. With Pantharette, she gets another kitten, but it gets eaten by the mother when it is 2 days old. Unfortunately, her husband dies in 1965, forcing her to leave the ranch and move to an apartment in California. She gives the ALC to the San Diego Zoo. KinKin and Pantharette die of pneumonia. This ends her adventure and it would not be until 1980 before she made a restart.

In 1961, Jean Mill imports an ALC called Malaysia. The ALC feeling somewhat displaced on her ranch in Arizona, she decides to give it the company of a black tomcat. To her and (everyone else’s) surprise, the animals mate and a litter ensued of two kittens. The male kitten does not survive, but the female KinKin can be rescued and grows up with a litter of Himalayas. She bred KinKin back to the father (there was no other suitable available) and two more kittens were born: a nasty tempered daughter (Pantharette) and a son who sadly died after a fall. With Pantharette, she gets another kitten, but it gets eaten by the mother when it is 2 days old. Unfortunately, her husband dies in 1965, forcing her to leave the ranch and move to an apartment in California. She gives the ALC to the San Diego Zoo. KinKin and Pantharette die of pneumonia. This ends her adventure and it would not be until 1980 before she made a restart.

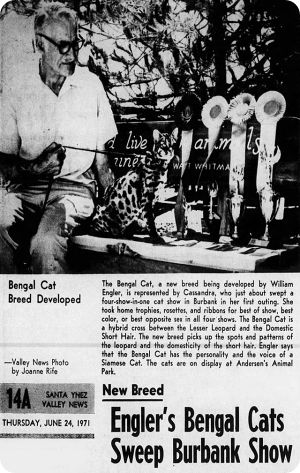

Bill Engler and his plea for cats

Another early pioneer of bengals was Bill Engler. He was a zookeeper and an active member of the Long Island Ocelot Club, the LIOC. In early 1964, Bill wrote a “plea for the cats” to LIOC members, stating that the number of exotic cats was declining rapidly due to population growth reducing their natural habitat, illegal hunting for their pelts and the demand for fur. There was little one could do about population growth, the demand for pelts was unlikely to diminish, and he also had no faith in public agencies and public officers to protect wildlife.

The only means he saw to save exotic cats was if they could be bred in civilisation like dogs and domestic cats. As regulations made importing, obtaining and selling these animals increasingly difficult, even for those fighting for their preservation, it was time to take immediate action.

The first hybrid litters come into the world

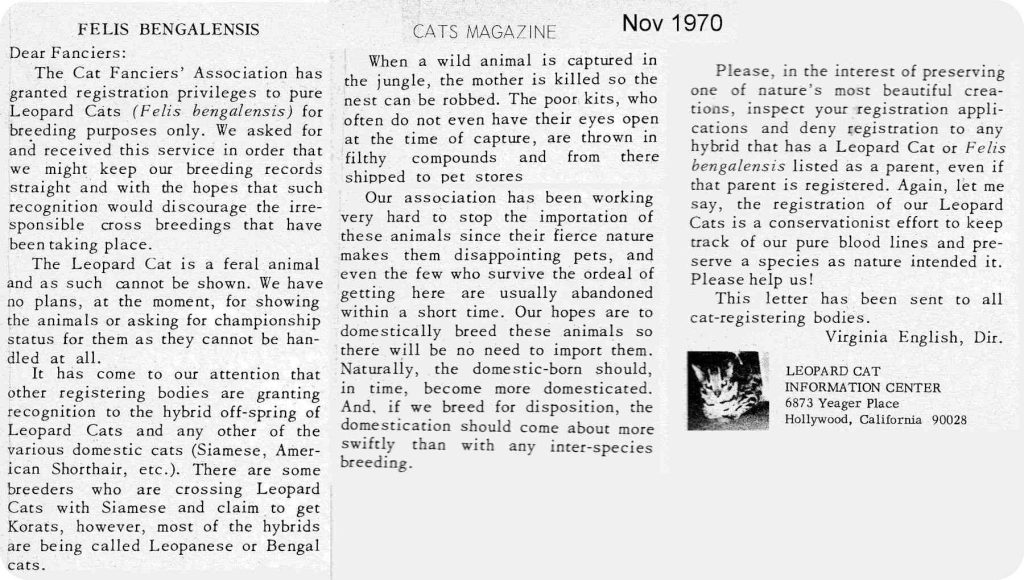

In 1970, Bill had bred two litters with his ALC Shah with a total of nine kittens. He wrote extensively about this in the LIOC newsletter in 1972, see article. By the way, breeding hybrid cats from ALCs (or other exotics) was not uncontroversial at the time. The wild nature of first-generation hybrid cats caused some resistance at the time from some breeders who, on the one hand, were afraid, that these animals would end up with people who could not provide proper care, or, on the other hand, saw no reason to bring this kind of mix-breed into the world at all.

In 1970, for example, the CFA even sent out a letter (see below) in which pure ALCs were allowed to be registered and allowed to be bred with, but the letter also makes a call to refrain from crossbreeding. By the way, the crossbreeds were already known as Bengal or Leopanese back then.

1: 1971 article on B. Engler’s show success with Bengals

2: 1970 article from CFA on breeding with ALCs and Hybrids

Generation 2.5 is bred for the first time

In April 1971, the females used for his first litters, Cybele and Cyclemnestra, were bred again to Shah, and they produced six more kittens. Bill stated that his goal for the hybrids was, “To create a small exotic cat that was beautiful and had has the disposition suitable for a pet house cat, that has a greater resistance to the diseases of civilization than its jungle-bred cousins, and that would readily reproduce itself.” In addition, he wrote, “I hope that these Bengals can not only help to close the gap between supply and demand of exotics, but also help to create a greater interest in all exotics, that this interest will be beneficial in funding research into the production of and legislation for the protection of all cats.” By 1975, he had bred more than 60 Bengals and reached “2.5” generations, or F2.5 kittens. Direct crosses between wild and domestic cats are called “F1” generations. A cross between an F1 generation and a domestic cat is called an F2 generation and so on. And crossing between an F1 and F2 generation is called an F2.5. The challenge of breeding these hybrids is, F1s and F2s often exhibit the wild behavior of exotics. In addition, mothers maim or eat their kittens, so the kittens must be taken away from their mothers immediately after birth to be raised by hand. Males are generally sterile until the F4 generation, which makes breeding a pure breed very difficult.

The name “bengal” is registered

Bill continued his vision, however, and presented the name “Bengal” to various cat associations and agencies, officially establishing the breed’s name. The name is derived from the Latin name of its wild ancestor, Felis Bengalensis– or Asian leopard cat, as it describes itself.

Bill continued his vision, however, and presented the name “Bengal” to various cat associations and agencies, officially establishing the breed’s name. The name is derived from the Latin name of its wild ancestor, Felis Bengalensis– or Asian leopard cat, as it describes itself.

The bengal breed was then the first to be accepted for registration with the ACFA (American Cat Fancier Association). Later, Bill reported that he managed to produce a number of fertile F3 males. On March 17, 1977, Bill died and his cats were taken over by friends in Florida. As far as we know, none of the current Bengals can be traced back to the Engler lines. William Engler, however, is the one known for establishing the name of the breed.

Jean Mill relaunches her breeding program

Back to Jean Mill. In 1975, she remarried Robert James Mill, who owns a one-acre horse pasture and a small orchard in the Covina hills. Despite his cat allergy, this gives her the opportunity to revive her breeding program. Her motivation is similar to Bill Engler’s. Many people are attracted to wild felines, but they are totally unsuitable to be kept by humans. By breeding a cat with the markings of a wild cat, but the character of a domesticated one, she could satisfy the demand and help protect cats in the wild. Or as she put it herself in an interview with the LA Times “A lot of people would like to have wild animals, but I don’t believe they should be allowed to have lions and tigers in their homes, and I thought that if I could breed a cat that looked wild but acted domestic, that would be a happy solution.”

W. Centerwall conducts leukemia research with ALCs

The third main character is Willard Centerwall. Dr. Willard Centerwall is a geneticist doing research at Loma Linda University on the feline leukemia virus (FLV) in the 1970s. For his research, he uses ALCs because they appear to be resistant to FLV. He wanted to investigate whether the ALC transmit resistance to their hybrid offspring after crossing with a normal cat and what part of the DNA is responsible for immunity. In addition, cat leukemia shares many similarities with human leukemia, so this study could provide useful results for the broader medical community. (It must be said that bengals are not immune to FLV). After Willard obtained a blood sample from the F1s for his research, he was looking for a new home for them.

Willard Centerwall delivers Jean hert first F1 females

In 1980, Jean Mill is trying to secure an ALC. She contacts Capt. Zobel of California Fish and Game who refers her to Centerwall. Jean obtains four cats from him: Liquid Amber (3/4 ALC), Favie, Shy Sister and Doughnuts. Later, she gets 5 more cats from Gordon Meridith who had previously received cats from Willard for her zoo in the Mojave Desert, but had to give them away due to serious illness. These were Praline, Pennybank, Rorschach (a grayish charcoal), Raisin Sunday and Wine Vinegar (who would later eat her only kitten). She was also offered F2, but turned them down due to lack of space and her unawareness of how difficult it would be to breed further generations.

Cat Millwood Tory of Delhi is the ancestor of the bengals

Now that she had nine F1 females, she started her search for a suitable male to mate them with. But what would be appropriate? Which genes would be useful, or dominant or would trash the bloodlines? She was reluctant to use any of the traditional purebred but (at the time) still genetically fragile cat breeds, such as the Mau, British Shorthair, Abyssinian or Burmese. During a trip to India in 1982, the curator of the New Dehli zoo took her to a beautiful spotted shiny golden domestic cat. This boy stayed mostly in the rhinos’ enclosure and, as a result, he did lose part of his tail when one of those behemoths stepped on it. After much red tape, the boy arrived at Los Angeles airport in a mahogany crate marked “said to be domestic cat.” She named him Millwood Tory of Delhi and registered him as Egyptian Mau (she calls her cattery Millwood). This male is one of the founding fathers of the bengal breed we know today with his distinctive pattern and shiny coat. He is pictured on the left along with Praslin, Pennybank and Rorschach. Tory of Delhi has also been frequently used by Mau breeders to improve the breed. In the years that followed, Jean imported several more “Indian” Maus for her breeding program to mate with her F1, F2 and F3 females. The early years were not easy and the F2 and F3 generation kittens were few and far between. In 1983, Destiny was born to Delhi and Praline and was the world’s first fertile F2 male. He was crossed with a Polyspot (also F2) and got a kitten Silk ‘n Cinders, with a shimmering golden fur without the usual ticking. A month later, out of Praline and Destiny, the male Aries was born with a similarly beautiful coat.

Tory of Delhi has also been frequently used by Mau breeders to improve the breed. In the years that followed, Jean imported several more “Indian” Maus for her breeding program to mate with her F1, F2 and F3 females. The early years were not easy and the F2 and F3 generation kittens were few and far between. In 1983, Destiny was born to Delhi and Praline and was the world’s first fertile F2 male. He was crossed with a Polyspot (also F2) and got a kitten Silk ‘n Cinders, with a shimmering golden fur without the usual ticking. A month later, out of Praline and Destiny, the male Aries was born with a similarly beautiful coat.

Female Penny Ante is the first famous bengal

In 1986, Penny Ante was born to F1 Pennybank and F2 Trademark (son of F1 Praline and Tory of Delhi). Penny is seen by Jean as the cat who founded the bengal breed. She looked more like a little leopard than any hybrid, and she was incredibly friendly and sweet at all 27 cat shows she attended. Her photos go around the world advertising shows from Seattle to Düsseldorf to Paris. And visitors line up at the show to watch her.

In 1986, Penny Ante was born to F1 Pennybank and F2 Trademark (son of F1 Praline and Tory of Delhi). Penny is seen by Jean as the cat who founded the bengal breed. She looked more like a little leopard than any hybrid, and she was incredibly friendly and sweet at all 27 cat shows she attended. Her photos go around the world advertising shows from Seattle to Düsseldorf to Paris. And visitors line up at the show to watch her.

She bought plane tickets to attend crucial cat meetings, started the Bengal Bulletin for breeders, wrote the standard, organized dinners for bengal exhibitors and judges, wrote countless articles for magazines, invited the media to photograph her cats, and answered a non-stop stream of phone calls day in and day out.

Jean Mill achieves her goal

After advocating acceptance of the breed at various cat breed associations, her work paid off when she registered 14 cats with The International Cat Association (TICA) 1986. TICA (the largest cat association in the world) also establishes a breed section for bengals in that year and gives permission for generation F4 and further to be allowed at shows. Jean initially registered her cats as Leopardettes, because she felt that fit her purpose better and she was afraid that people would associate the name bengal with the appearance of a tiger.

After advocating acceptance of the breed at various cat breed associations, her work paid off when she registered 14 cats with The International Cat Association (TICA) 1986. TICA (the largest cat association in the world) also establishes a breed section for bengals in that year and gives permission for generation F4 and further to be allowed at shows. Jean initially registered her cats as Leopardettes, because she felt that fit her purpose better and she was afraid that people would associate the name bengal with the appearance of a tiger.

At first this was accepted because her cats had no relation to Bill engler’s lines, but soon it led to confusion at Tica. She then suggested calling cats up to generation F3 “bengal” and the generations and F4 and later “leopardettes” to distinguish between the still wild “founding generations” and the already domesticated variety. However, this proposal was not accepted and the name bengal was chosen to designate the breed regardless of generation.

Jean Mill continues her breeding program for another 20 years

In 1987, Jean Mill bred her first “Marble” which she named Millwood Painted Desert. She writes: “1987, another surprise! Cinders and Torchbearer had an astonishing new kind of kitten. She was a spectacular little female with an odd soft, cream-colored fur and an odd weird pattern that looked like drizzled caramel. At the Incats show at Madison Square Garden, and throughout the country, she was a sensation!!! The judges were overcome by her beauty and my cages were inundated with people wanting a glimpse. Most liked her better than her spotted cousin, Jungle Echo. I hadn’t intended of including anything other than spots in my first standard, but ‘by popular demand’ ther marbles were added.” Around 1989, Millwood established new lines with the ALCs Kabuki and Cameo.

She continued her work for 20 more years until she turned 83 in 2009. She died in 2018 at the respectable age of 92. Where Bill Engler had reached F3 generations, Jean Mill continued her program and also produced F4, F5, F6 and later generations that had the desired character of a normal breed cat but with a markings of an exotic cat. With this, she can rightly be called the founder of the modern bengal breed as we know it today.

Recognition of bengals by TICA

In 1986, bengals were placed on the TICA list of experimental breeds and accepted for exhibition. In 1991 the black tabby spotted (brown) bengal was recognized for championship status by TICA and in 1993 the marble tabbies and snow variants followed. In 2005, the silver bengal was admitted to the championship status in TICA. Brown Bengals come in various shades, including cream, golden, honey, taupe, caramel, beige, tawny, caramel, cinnamon and brown. Silver bengal cats are characterized by a background coat that has no color, although marbling and rosettes may appear in various shades. Snow bengals can be further divided into seal sepia, seal mink and seal lynx point. Two accepted spotting patterns apply to Bengal cats of all coat colors: spotted (spotted) and marbled (marbled). Breeders have developed several varieties, including charcoal, blue and melanistic (almost entirely black color) bengal cats. Finally, there is now even a long-haired version, the Cashmere bengal cat. The counter of number of registered bengal catteries stood at 125 in 1992. Around 2000 there was a jump in popularity and by 2019 there were more than 1,000 bengal catteries registered with Tica.

So much for the history of bengals, where over the past 40 years the bengal cat has been bred from the first hybrids into a beautiful cat with one of the most striking coat patterns of any breed, a curious and adventurous characteristic and an affectionate nature. However, in the last 15 years, the development has progressed. Whereas in the early 2000s bengal had mostly spotted markings, through selected breeding this has developed into a coat with sharp markings with so-called rosettes.

New cat breeds are being developed from bengal

Because of its striking appearance, the bengal is now also being used to develop new breeds with a wild appearance:

- The Serengeti cat: developed from crosses of the bengal with an eastern shorthair, with the goal of producing a domestic cat that mimics the appearance of an African Serval, without actually incorporating serval genes through hybridization.

- The Savannah: a cross between a bengal and a serval.

- The Toyger: developed in the 1980s by Judy Sugden (Jean Mill’s daughter!) by crossing the bengal Millwood Rumpled Spotskin with a short-haired domestic cat named Scrapmetal in an attempt to obtain the tiger’s spot pattern.

- The Cheetoh: created from a cross between bengals and ocicats.

This brings us to the end of this article about the origin of the bengal breed. References used and sources for further reading are listed below.

References and further reading

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bengal_cat

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Mill

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Felid_hybrid

https://web.archive.org/web/20190314055459/http://www.bengalsillustrated.com/bengal-cat-history/

https://archive.org/details/ourcatsallaboutt00weir/page/54/mode/2up?view=theater

http://www.bengalpedigrees.com/old/Millwood/scrapbook.php

http://www.bengalpedigrees.com/old/Millwood/milestones.php

http://messybeast.com/small-hybrids/hybrids.htm

http://messybeast.com/small-hybrids/bengalensis-margay-hybrids.htm

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-03-10-ga-32170-story.html

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-09-17-ga-8687-story.html

Long Island Ocelot Club bi-monthly newsletters from 1964 to 1977 via www.felineconservation.org

Digital archives of Loma Linda University: https://cdm.llu.edu/digital/collection/photodb/search/searchterm/centerwall

https://www.tica.org/breeds/browse-all-breeds?view=article&id=824:bengal-breed&catid=79.